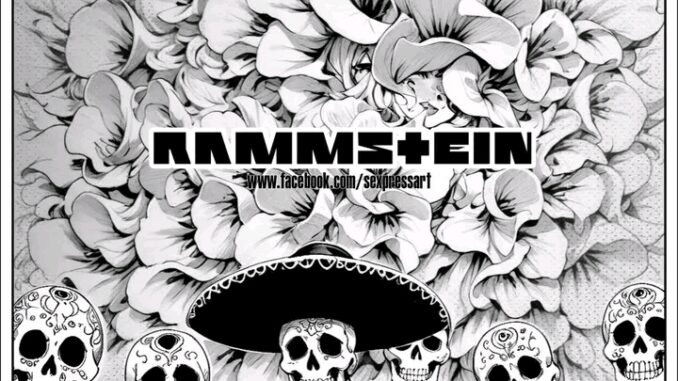

Day of the Dead: A Tribute to Rammstein’s First Album

The Day of the Dead, or Día de los Muertos, is a celebration that dances between the sacred and the profane, between silence and fire. It is a festival of memory — a dialogue with those who came before us, adorned in marigolds and lit by candlelight. Yet, in the flicker of that light, there is something hauntingly familiar to the industrial aesthetic of Rammstein’s first album, Herzeleid — an image of raw humanity, stripped to its essence, confronting both beauty and decay.

Rammstein’s debut cover, with its stark portrayal of the band’s members as near-mythic figures — bare-chested, emotionless, and almost funereal — evokes the same tension found in the Day of the Dead. Both present the body as a vessel of mortality and transcendence. The album’s mechanical aggression, pulsing like an iron heart, mirrors the rhythmic beating of drums in a cemetery procession. There’s a shared defiance in the face of death: not fear, but fascination; not mourning, but ritualized remembrance.

To pay tribute to Herzeleid through the lens of Día de los Muertos is to fuse two languages of intensity — German industrial steel and Mexican spiritual color. Imagine the band’s faces painted as calaveras, their solemn expressions transformed into skull masks traced with delicate filigree. Around them, instead of cold machinery, bursts of orange cempasúchil flowers, paper banners trembling like fragile lungs in the wind. The marigolds’ scent replaces the smell of oil and smoke, yet both speak of transformation — the body turning to dust, the machine rusting away, the song outliving both.

Rammstein’s music, particularly in Herzeleid, thrives on contrast: tenderness smothered by noise, love corrupted by machinery, life shadowed by death. That same duality pulses through the Day of the Dead — a celebration that laughs in death’s face while offering it a seat at the table. There is beauty in the grotesque, power in decay, and peace in remembering. Both worlds understand that to acknowledge death is to honor life.

In this imagined convergence, Herzeleid becomes an altar — a cold steel shrine surrounded by candles and skulls, where guitars wail like mourning voices and drums pound like hearts refusing to stop. On the Day of the Dead, Rammstein’s debut would not sound foreign. It would sound eternal.

Leave a Reply